On 23 April 1616 Shakespeare

died; he was fifty-two. Not surprisingly, his plays have been translated into

every major living language and are performed more often than those of any

other playwright.

Controversy has lingered over the

authenticity of some of his works. I decided to play (!) with this idea for a

science fiction story, ‘If We Shadows Have Offended’, which can be found in the

collection Nourish a Blind Life

(2017).

The story is set in 2093 and concerns Zeigler, who has

gained approval from the Time Door Committee, to research a specific event in

the past. Here’s an excerpt:

He

smiled at his great ancestor’s photograph. In 1895 WG Zeigler, a Californian

lawyer, had been the first to suggest that Christopher Marlowe’s death on 30

May 1593 was staged and that the poet actually went underground to write the plays

using Shakespeare’s name.

Now, at last, he would be able to prove once and for all whether

or not Shakespeare had written everything attributed to him.

***

The

twelfth night arrived.

In the greying mackerel sky, the sinking sun streamed red down

onto the white concrete square building with a circular tower, similar in style

to the old-fashioned long superseded light-houses. Above the tower hovered a

shimmering black cloud. But this was no ordinary cloud. It hung perpetually

over the tower, possessing no depth or discernible edge. Gleaming. Apparently

as fathomless as the deeps of the oceans.

One of several Timedoors into

the past.

Zeigler had frequently passed this and other Timedoors, and on each occasion he had been drawn by the weird unearthly

sight of those black clouds. Such awesome power, so frightening to contemplate,

and now he was destined to travel through one.

He stood outside the door marked ENTRANCE. Above was a plaque with

a quotation, ironically from Shakespeare:

‘The end crowns all,

And that old common arbitrator, Time,

Will one day end it.’ - Troilus and Cressida

Zeigler

read the small red print alongside the doorway.

He was to give his name, age, occupation, ID number, and his

appointment reference number. Making sure he got it in the right order, he

complied.

The door opened upwards with a hiss.

The interior was blank metallic walls on three sides bathed in

glowing red light.

A faint humming reached him as he entered. He hardly noticed it.

His was the last generation not to live wholly in an electronic, mechanical

world together with its concomitant noises. He could still remember when

silence was accessible on the planet. It was an irrational thought, but he wondered

what the next-but-one generation would do if confronted with total silence. He

shuddered to think and recalled Coriolanus:

‘My gracious silence, hail!’

By then of course they might be virtually deaf - his nephew’s

hearing was 30% poorer than his, and the lad was average for his age.

The door glissaded shut behind him.

The pitch of humming heightened. If the slight upsurge of his

entrails was anything to go by, he was rising in a remarkable lift - no, there

was no lift cubicle: he was rising bodily up a shaft, probably in some kind of

anti-gravity beam.

The instructions had been unable to prepare him for anything like

this, doubtless for security reasons.

Markers on the walls showed his ascent. At the fifty-foot mark he

stopped with a queasy reaction in his stomach.

An opening appeared in front of him and he stepped into a brightly

lit circular room, the walls crammed with computer facia and attendant

hardware. Seated at a tubular steel desk, a young beardless man in a white

smock beckoned for Zeigler to step forward.

The young man’s ample stomach pressed tightly against the coat,

reminding Zeigler of Henry VIII: ‘He

was a man, Of an unbounded stomach.’

‘You are on time, Mr Zeigler - a trait sadly lacking these days!’

The man shoved across a quarto printed sheet. ‘Please read this and sign. It is

the Official Secrets Codicil (TPC) 2058. Afterwhich,

kindly enter that stall over there.’ He pointed to a recess in the wall,

between two orange steel computer cabinets.

The cubicle was uncomfortably narrow.

‘This won’t hurt, Mr Zeigler. But we have to be sure you are the

real you! And, you see, access to the Timedoor is only permitted if you’re

completely fit and germ-free.’

A flash appeared in front of his eyes. It felt as though his

eyelashes had been seared off. But it was over so fast he remained unmoved.

Zeigler found that the man with an unbounded stomach was blurred.

‘Yes, Mr Zeigler, your physiogram matches with State records. You have also

been made bacteria-free. Your unique bacteria, however, will be coated back

onto you when you return. Be careful while in Elizabethan England, sir, for you

are now exceedingly vulnerable to illness of any kind.’

‘Haven’t you any panacea-type injection you could give me?’

‘No, the side effects while undergoing the time-journey are

deleterious in the extreme. We lost two esteemed pioneers that way - they were

devoured from the inside by various bacteria that grew to huge proportions. As

yet we don’t know why - but at least we detected it. This is another very good

reason why you’ve signed this piece of paper, Mr Zeigler.’ The man wafted the

form and smiled; he was not so blurry an image now. ‘Not a word, mind. To

anyone. You will be free to report on your findings only. The rest will be

erased from your mind once the report is filed and copyrighted; however, any credit

will be yours entirely.’

‘I never realised how - delicate, no, how dangerous - this

time-travelling is. It puts me in mind of The

Merchant of Venice: “Men that hazard all, Do it in hope of fair

advantages”.’

‘Really, sir? And what’s your “fair advantage”?’

‘Oh, confirmation of my research paper, to vindicate an ancestor.’

‘I see. Well, we’re meddling with things our ancestors only

dreamed about, Mr Zeigler. Our fail-safes even have fail-safes, hence this

little gadget.’

The young nameless man held up a small black box. ‘Please remove

your shirt, sir. Here is a pamphlet about this little beauty. Read it

carefully.’

Although very curious as to why the box was being secured over the

fleshy bulge of his left shoulder blade, Zeigler scanned the pages of small

print.

It appeared that the device would self-destruct should he do

anything to disturb the balance in the past. By self-destructing, it would also

take him with it, leaving no trace whatsoever. Then the Timedoor would close on

his ashes and the pod would disintegrate.

Connected remotely to the box was a pendant, an eye. The man

draped this round Zeigler’s neck. ‘The simple act of removing the eye or

breaking it will also result in the box self-destructing.’ He shrugged

apologetically. ‘We must protect ourselves as well as our past.’ He grinned.

‘Selfish maybe, but I wish to continue in existence!’

‘You mean some applicants might seriously contemplate disrupting

the past to change the future? Don’t they realise they’d be putting their own

existence in jeopardy?’

‘Some fanatics think it worth the risk, Mr Zeigler.’

Zeigler went cold and thought how chilling the words from Richard

II were in this context: ‘O! call back yesterday, bid time return.’

‘Right, Mr Zeigler, now you are ready. Please stand on that

circular brass plate.’

Zeigler was lifted up another anti-gravity beam. ‘Enjoy your trip!’

called the young attendant.

Again, Zeigler rose but this time it was a green zone: olive and

yellowish. Quite sickly.

Finding himself in another room devoid of furniture or machinery,

he was startled to hear a metallic female voice issuing from a grille.

‘The parcel you dispatched separately in accordance with

instructions has been examined and you may now put on the clothes. You have

chosen a particularly smart set of garments, sir.’

The speaker unit clicked off and a tray levered out from the wall

with his pile of Elizabethan clothes lying on its shiny surface.

Irrationally, he felt self-conscious as he undressed; simply

because the metallic voice sounded female?

He took a while to slip into the clothes, all the while conscious

of the presence of the black box.

The voice returned. ‘Now step back into the shaft. Don’t look

down, don’t worry - the ag’s still on!’

Zeigler was not amused. But he didn’t look down; his ruff made

that action awkward anyway.

Up again. To the 140ft mark.

‘Alight, please.’ A flesh-and-blood woman’s voice.

This room was roofless and possessed a central dais on which

rested a conical transparent pod. The pod was aimed upwards, pointing at the

black hole. Even from this close, the true edges of the Time Hole were not

readily discernible. The shimmering effect made him dizzy.

‘Step this way, please, Mr Zeigler,’ said an attractive brunette

attendant also dressed in white. She possessed angelic features, which he thought

somehow appropriate up here.

She eyed his prominent codpiece, arched her eyebrows suggestively

and smiled.

He blushed; another first-impression destroyed: I thought her as

chaste as unsunn’d snow - Cymbeline.

He sighed.

Gently the woman placed Zeigler inside the pod. Although the pod

was designed for bigger men than him, it was still a tight squeeze, mainly due

to his doublet bulging with the bombast stuffing of the period.

‘Everything all right? You require any paper of the period for

notes, or a recorder can be fitted to the “eye” if you like?’

Zeigler shook his head. ‘No, thanks. I’m only after one fact. Have

you been able to pinpoint - select the right…?’

‘Yes. May 30th, 1593. Almost 500 years ago to the day, Mr Zeigler.

We’ll put you down just outside the town. There’s ample room to conceal the pod

in a neglected grove nearby.’

He craned his neck. ‘Are those the screens that you view me on -

through the eye, I mean?’

She nodded, then said in a serious tone, ‘Take care, Mr Zeigler -

we can’t help you once you leave the pod.’

‘I know,’ he said solemnly, his stomach performing somersaults. ‘I

know all the risks. But our faculty must find out if - well, you know my

theories, anyway.’

‘Yes. Now I’m going to lower the cowling and secure you inside.

You’re liable to feel excessively giddy and you may even lose consciousness for

a short while. Our scanners show you obeyed instructions and didn’t eat today -

so your ride should be an untroubled one. I trust it will also be successful,

sir.’

‘Thanks.’ He smiled.

And she shut him inside.

It was most peculiar, how he suddenly felt trapped, though he

could see all round. He closed his eyes, calmed himself. Mustn’t get excited.

Be rational, logical. Simply observe.

‘Ready?’

‘Yes.’ His voice came out as a strangled croak.

He felt as though his whole face was suddenly being squeezed off

his skull as the pod fired up, the G-forces ramming him hard into the ergonomically-shaped

cushioned seat.

Contrary to his original conception, he was not immersed in

absolute blackness on entering the Time Hole.

It was like a velvety blue-black, with pinpoints all around, like

stars that had forgotten how to twinkle. The sensation of movement had stopped

- how long ago? He had no way of knowing, there were no instruments or clocks

in here; and his wristwatch had been removed, together with every other

personal possession.

Another quotation, from As

you like it, reared its head for him to muse upon: ‘Time travels in divers

paces with divers persons.’

Dizziness gnawed at the edges of his consciousness but never posed

a serious threat. Elation kept him awake. He would succeed where so many before

him had failed!

Over the years, anti-Stratfordiana had grown to a flood.

Professor Thomas C Mendenhall counted the letters in 400,000

Shakespearean words, discovering that for both Shakespeare and Marlowe the

‘word of greatest frequency was the four-letter word’, a fact that left the

world of letters decidedly unshaken.

Then in 1955 Calvin Hoffman sought documentary proof for his case

in the tomb of Sir Francis Walsingham, Marlowe’s reputed homosexual lover. But

nothing was found in the tomb. Not even Sir Francis.

Which shouldn’t have come as a surprise, Zeigler reasoned.

Walsingham had contrived a most corrupt system of espionage at

home and abroad, enabling him to reveal the Babington plot which implicated

Mary Queen of Scots in treason, and to obtain in 1587 details of some plans for

the Spanish armada. Queen Elizabeth I acknowledged his genius and important

services, yet she kept him poor and without honours, and he died in poverty and

debt in 1590. At least he seemed to live longer than Marlowe.

The twenty-nine-year-old son of a shoemaker, Marlowe had died with

a dagger in his brain, the precise circumstances quite obscure.

Marlowe had from time to time been engaged in government employ, a

euphemism for secret service work, and had become embroiled in the theatre of

conspiracy and intrigue, the tumultuous, often dangerous life of London’s

underworld.

At the age of twenty-one, Marlowe was employed as an agent

provocateur, posing as a Catholic to spy on other Catholics, and acted as a

renegade to trap such people.

He did it for the money, insinuating himself into the households

of Earl of Northumberland and Lord Strange. As a projector he actively fostered

treason in the employ of Sir Francis Walsingham and later of Sir William Cecil

Burghley.

Wily young Marlowe’s apparent atheism was just a ruse for trapping

free thinkers into indiscretion. Finally, he was set up as a conspirator by the

Earl of Essex as a way of striking at Sir Walter Raleigh.

On that fateful night, Marlowe was knifed over his right eye in a

drunken brawl at a tavern in Deptford, but the swift pardon of his murderer,

Friser, twenty-seven days after the poet’s burial, suggested to Zeigler that

the death had other, possibly political, undertones.

Hoffman had believed the whole affair was staged by Sir Francis

Walsingham to remove his lover from the threat of imminent arrest for alleged

blasphemy and atheism. Hoffman argued that the coroner was bribed to accept a

plea of self-defence on behalf of Marlowe’s alleged killer and docilely

accepted the stated identity of the body.

Hoffman believed Marlowe settled on the Continent and continued to

write and sent his manuscripts to Walsingham, who had found a reliable if

dull-witted actor fellow, William Shakespeare, ready - for a stipend - to lend

his name as the author of Marlowe’s works.

As Walsingham had apparently died two years earlier than the

Deptford incident, Hoffman’s theory was far from acceptable, but it suggested

other similar possibilities to Zeigler.

Since most of Shakespeare’s plays were written after the recorded

death of Marlowe, Marlovian theorists must prove Marlowe lived after the

Deptford incident in order to write the plays.

Marlowe had been deeply influenced by the writings of Machiavelli,

so any intrigue along these lines would most certainly appeal to him.

Other contenders over the years for the mantle of “greatest writer

in the English language” included Sir Francis Bacon (died 1626), Edward de

Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (died 1604), Sir Walter Raleigh (died 1618), Michel

Angelo Florio (died 1605), Anne Whateley (died 1600) and even Queen Elizabeth

herself (died 1603). As Shakespeare’s last known work The Tempest was attributed to 1611, the literary prowess of some of

these contenders can be marvelled at, Zeigler thought, capable of even writing

beyond the grave.

In the latter part of last century, computers had been used to

join in the academic fray.

Shakespeare databases were built as early as 1969 on an ICL

machine, the KDF-9. Since then, ICL’s Content Addressable File Store -

Information Search Processing and Oxford’s Concordance Program, written in Ansi

Fortran had been used to word-count and create concordances, ostensibly to

facilitate research. The DEC VAX 11/70 computer research gave credit to

Shakespeare for Acts Four and Five of Pericles

but not Acts One and Two; the researcher or computer never mentioned Act Three!

Certainly in the world of letters it was a controversial theory

and Zeigler had some sympathy with Shakespeare. Lines from his Venus and Adonis seemed apt:

‘By this, poor Wat, far off upon a hill,

Stands on his hinder legs with listening ear,

To hearken if his foes pursue him still.’

Zeigler

wondered if Shakespeare waited still, far off on some heavenly hill, wondering

if his detractors would ever cease pursuing him.

Poor Will, thought Zeigler. Well, the Timedoor Committee evidently

felt the Zeigler theory had sufficient merit for them to accept his research

request. And now he was almost there!

After

some time, Zeigler noticed a lighter patch ahead, getting bigger. The

indefinable edges again, the tint of a dusky sky...

He didn’t recall passing through the hole or landing. Perhaps he

simply materialised?

Darkness. Raised jaunty voices. The rank stench of open sewers.

These were his first impressions. It was night. He looked around and discovered

he was still lying in the pod amidst a grove of bushes.

He checked the two console buttons. Red for his return signal.

Green for opening the pod. Another button, on the reverse of his eye-pendant,

worked the pod’s entrance-hatch for ingress.

Zeigler operated the green button and no sooner had he stepped out

than the hatch shut behind him.

As he walked a few paces out of the bushes, he glanced back and

was surprised to find he could no longer see the pod; its see-through

capabilities aided concealment: someone would have to virtually stumble over it

to discover the craft’s presence.

He didn’t have far to walk before he came to the town with its

tumbled toppling street, black and white timber awry, cobbles threatening to

pitch him every which way. Cats fought for thrown out fish-heads and other

unidentifiable scraps.

Zeigler felt very vulnerable strolling the streets, for in these

times no man was safe from the reach of the torturer or the smell of the

dungeon. A carrion odour blew towards him and he retched emptily: ahead he noticed

the swaying hanging remnants of a human being; some of the hideous butchery on

the scaffold was sufficient even to turn the stomach of an Elizabethan crowd.

A building belched forth the soul of an alehouse but, gagging on

the riot of smells, he passed it by. He needed to find Mistress Turner’s

lodging house, up a squeeze-gut alley.

***

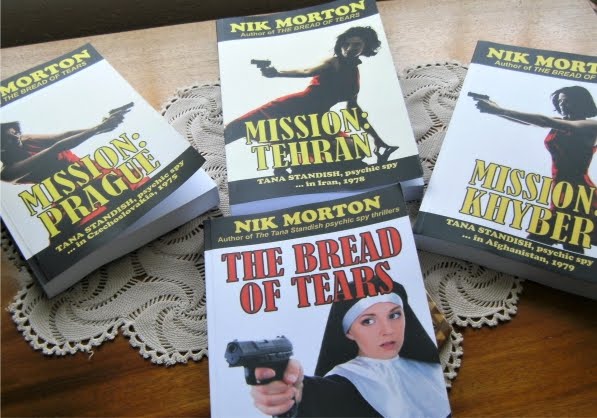

The full story can be found in the collection

of 21 tales, Nourish a Blind Life (paperback and e-book)

The title story won a prize; the judge stated:

‘I read a lot and like to think that

I’m fairly hardened to the human experience. Your story Nourish a blind life however, moved me enormously. With a powerful

understanding you avoided any mawkish melodrama. The ending, although sad, gave

satisfaction knowing the narrator was soon to be free! Thank you.’ – Eve

Blizzard, judge

***

The full story was published in my blog on 23 April and 24 April 2016 on the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death.